Node.js, Web API, and RabbitMQ. Part 3

October 11, 2014

Desiring to learn about both Node.js (particularly as an API server) and ASP.Net Web API, I decided to throw one more technology in the mix and see which one is faster at relaying messages to a service bus, namely, RabbitMQ.

Part 1: Test Runner

Part 2: Initial Node.js Code

Part 3: Web API Code

Part 4: Enhanced Node.js code

Part 5: Performance Comparison

And now, I finally get back to blogging about the ASP.Net Web API code that I wrote for this head-to-head comparison of REST service and message bus integration. The official tutorials were my guide for Web API, and as with the test runner in part 1, I used MassTransit as a convenient library for publishing from .Net code to RabbitMQ. Owin was my solution for self-hosting the web application.

With Owin integration, a Web API server starts with one line of code invoked from the hosting application: _webService = WebApp.Start. Let's take a close look at that Startup class, shall we?

public class Startup

{

public void Configuration(IAppBuilder appBuilder)

{

if (appBuilder == null)

{

throw new ArgumentNullException("appBuilder");

}

var config = new HttpConfiguration();

config.MapHttpAttributeRoutes();

config = SetupContentHeaders(config);

config = SetupDependencyInjection(config);

appBuilder.UseWebApi(config);

}

private static HttpConfiguration SetupDependencyInjection(HttpConfiguration config)

{

var container = new UnityContainer();

container.RegisterInstance(InitializeServiceBus(), new ContainerControlledLifetimeManager());

config.DependencyResolver = new UnityResolver(container);

return config;

}

private static HttpConfiguration SetupContentHeaders(HttpConfiguration config)

{

config.Formatters.JsonFormatter.SupportedMediaTypes.Add(new MediaTypeHeaderValue("text/html"));

return config;

}

private static IServiceBus InitializeServiceBus()

{

var serviceBus = ServiceBusFactory.New(sbc =>

{

sbc.UseRabbitMq();

sbc.ReceiveFrom(Settings.ServiceBusAddress);

sbc.DisablePerformanceCounters();

});

return serviceBus;

}

}

In summary, this class configures Web API with:

- attribute routing

- Unity as my dependency injector of choice

text/htmlas the supported mime type for content transfers- Open a connection to the Rabbit service bus and inject it into Unity for use in the API service method

But you could probably read and figure that out. The key thing here is getting the service bus setup in the dependency injector. When a call is made to the API, Web API instantiates a controller and each controller instance will use this service bus class. And that makes me think that I should investigate cleaning up my Node.js code – it is not using dependency injection, and it is opening and closing the service bus connection with every API call. Can't be good for efficiency.

And now, the controller:

public class MessageController : ApiController

{

private readonly IServiceBus _serviceBus;

public MessageController(IServiceBus serviceBus)

{

_serviceBus = serviceBus;

}

[Route("Message/{message}")]

public HttpResponseMessage Get(string message)

{

SendToQueue(message);

return new HttpResponseMessage(HttpStatusCode.Accepted);

}

private void SendToQueue(string message)

{

_serviceBus.Publish(new SimpleMessage { Content = message });

}

}

As with the Node.js service, you can see that the service accepts messages routed to http://baseAddress/Message/{message} or /Message/:message as Node has it. Same concept here. Because .Net is my bread and butter, I didn't scatter debug statements throughout this code, as I did in the Node version. In a real world application, I would certainly include error and trace logging here.

Sending a message to the service bus through MassTransit is quite easy. As with the Node code, the method returns HTTP status code 202 ("Accepted") to the requester. Arguably this could have been status code 200. However, since this is mere toolkit experimentation and not an actual API, the precise semantics of HTTP status codes – and GET vs POST (or PUT, PATCH, etc) – are not important.

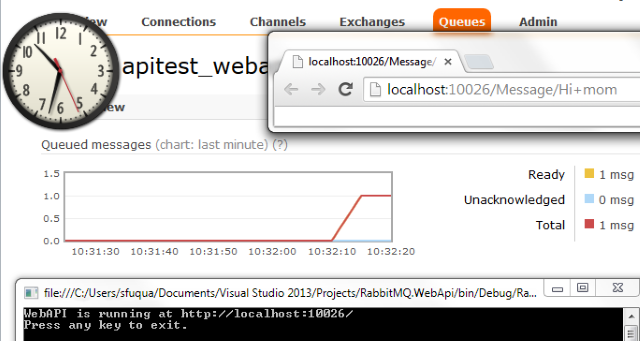

This time, the test is green: a message sent to the API is forwarded to Rabbit and can be consumed by the MassTransit-based test helper class, documented in part 1. Let's look at this in action: open a browser window, type a message-formatted URL, and watch it show up in the message queue:

And here is the message in the queue. Note that it is in the apitest_webapi_error queue, with _error appended. This is because I have a MassTransit-based subscription to this queue, but I don't have any consumer running for this message type. The result is that the message is pulled from the queue by MassTransit, but then pushed right back to Rabbit in this error queue.

Exchange apitest_webapi_error Routing Key Redelivered ∘ Properties

message_id: db190000-2f82-40f0-69d4-08d1b37f1e1e delivery_mode: 2 headers:

Content-Type: application/vnd.masstransit+json Payload 291 bytes Encoding: string { "destinationAddress": "rabbitmq://localhost:5672/RabbitMQ.WebApi:SimpleMessage", "headers": {}, "message": { "content": "Hi+mom" }, "messageType": [ "urn:message:RabbitMQ.WebApi:SimpleMessage" ], "sourceAddress": "rabbitmq://localhost:5672/apitest_webapi" }

No TrackBacks

TrackBack URL: http://www.safnet.com/fcgi-bin/mt/mt-tb.cgi/135

Leave a comment